Homing by Helena Michie

NOW WITH GYNOPHOBIA!

Disaster Tourism

It begins very soon after the winds die down and the rain stops. You get in your car that you may not have remembered to fill with gas before the storm and drive around your neighborhood looking for what Harvey, or Ike, or Beryl, or the unnamed derecho has wrought. When you first started to do this, maybe 15 years and 10 major storms ago, you called it “damage assessment,” as if this were the first step in doing something about it. Now you know it under less self-aggrandizing names. Voyeurism. Nosiness. Schadenfreude, the guilty (and fleeting) pleasure of seeing that some people are worse off than you are. The phrase “Curiosity Crawl” that so aptly describes the people who cause traffic jams on one side of the road when there has been an accident on the other. Over the years, you have settled on “Disaster Tourism.”

The Things We Bring With Us

In my mind, I am always facing the sea, looking out towards the horizon. It could be late afternoon; there may be heavy-beaked pelicans dropping suddenly from the sky when they see a fish in the waves. I count them as I once counted sheep; there are bombers who fall like meteors, skimmers who swoop along the crest of fish-fat waves, and paddlers who sit heavy-bottomed in the surf. Or it might be eerily still, no birds, and thus, my fishing husband reminds me, no fish, the Gulf deserted, the waves as they break empty of visible life. It could be dawn, the sun a copper globe in the east, moving inexorably through a field of fuchsia clouds. Sometimes, in my fantasy and anticipation, it is night and there is a moon path on the water pulling with its cosmic force the naked crabs as they scuttle from their holes in the sand towards the dark sea.

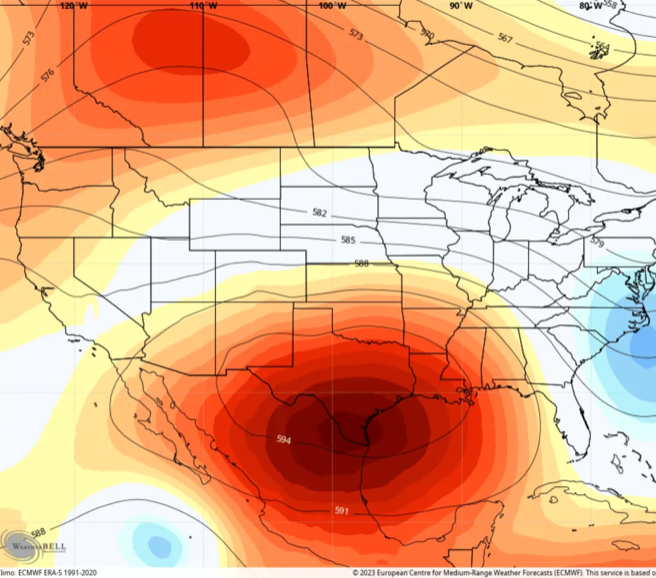

Heat Dome

The sky in Texas, even in the middle of a city like the city Houston, is almost always a blue dome. This is its magic. Since moving here, I have brought images of that sky with me as I travel. I look up at the ceiling of the Sistine chapel and see, for the first time beyond the figures, not just blueness, but the shape, its topmost curve just out of reach of my fading eyesight and the camera lens on my phone. Looking up, the height of the ceiling registers in the strain of my neck; the blue comes cascading down to meet and soothe me. It is not—quite—that I am enveloped since I have to make a point of looking up, but I am, somehow included in the grand sweep of the design. The experience gets repeated in countless smaller and less famous churches, in Sicily, where the outside air can feel like Texas. When I enter a church, I walk slowly around the perimeter, and then back again to the entrance saving the dome above th altar for last. The painting could be figural: a Christo Pancrator holding a book, or a crucifixion scene, but sometimes there is just a painted sky full of stars.

Barbies

If you read Erica Rand’s wonderful 1995 book, Barbie’s Queer Accessories, you will come across the genre of the “Barbie story”—that is, adult women describing their relationship over time with Mattel’s signature doll. Perhaps surprisingly, most of the stories Rand cites, including the origin story of Barbie’s creation, begin with mothers. From Ruth Handler, Barbie’s progenitor, who, according to the official myth of Barbie’s origin, created the toy because she was dissatisfied with the “fashion dolls” available to her daughter, to the feminist mothers who resisted buying Barbie and her accessories, the stories, mostly from childhoods lived in the 1960s and 70s, center Barbie first in family systems and then later, as Rand’s title suggests, in wider communities that appropriate Barbie for their own purposes.

Mother Tongue

Italian was not my mother’s mother tongue. When she and my father moved to Italy in 1953 so, she took language classes at the Dante Aligeheri school for foreigners. When I heard tell of this as a child, the name of the school stuck in my head without further referent. The Inferno surprised in many ways; one of them was that it seemed to have been written by my mother’s teacher. Even as a young girl I was a little supercilious about my mother’s, to me, long ago lessons. I could not imagine her in a school situation. She had told me long before that she was not “good at school” and I believed her, smug in the knowledge that I was. My father and I shared, at least I thought so, a loftier Italian, more (but not terribly) grammatical. The truth was, of course, that my mother used her Italian in a way we did not have to. She bought fish from the fish man, tomatoes from the tomato woman, asked questions and argued with them. She had words for the various qualities a fish or tomato might or might not have, and words for bonding with the market stall owners over her pregnancy.

Lucy

When I thought about Santa Lucia, which was not very often until a few days ago, I thought first of how she appears in vaguely Scandinavian illustrations from children’s books and Christmas cards with:; part angel, part Christmas tree, she is a figure of innocence, wearing crown of candles on her blonde curls. In Tasha Tudor’s illustrations, she cavorts with corgis and cats. This Lucy in her white dress is not the patron saint of Syracuse. She is not the martyr whom her torturers attempted and failed to set alight after they tried and failed to drag her to a brothel. She is not the woman who gauged out her own eyes, the one so often represented in Renaissance art holding out her eyeballs on a plate or in a cup. She is not the victim who finally succumbed to having her throat cut. She is not even the heroine who rescued Christians from the catacombs, encircling her head with candles so she should see to help them escape.

Sensible Shoes

You are old. Yet, when confronted with the possibility of climbing a bell tower in an Italian church, you always say yes. This is true whether there is sign saying “100 steps” or 36, or 300. You also say yes to the panoramic terrace, usually about 40 additional steps, by which the signs mean not units on your apple watch but stairs, worn to slickness by fellow climbers over hundreds of years. You know, because this is always the case, that when you get to the top of the first set of, say, 100 steps and pause, panting, under an enormous bell made out of canon balls in earthquake country, that the second flight will be narrower, and will wind many times around a crumbling but somehow still slippery central pole. The view from the “panoramic terrace” will be exactly the same as the view from the campanile. You will see trees, mostly olive trees and those depressing firs that someone imported from Italy onto the Rice University campus to die. You will see innumerable domes and church roofs sparkling blue and copper in the sun. You will not be able to identify any of them for certain.

Bathroom Doors

But even for cisgender people, the alignment is imperfect. Although comfortable with being called a woman, I do not think of myself as a “lady.” Given a choice between “Ladies” and “Gentlemen”, if it were not for the urgencies of bathroom visiting, I might say “neither” or “no thanks.” I might choose to go elsewhere—but where? I am old enough to remember the feminist campaign to replace the phrase “Ladies’ Room” with “Women’s Room.” I can also remember Marilyn French’s novel The Woman’s Room derives its title from this struggle, and can see in my mind’s eye it’s cover, with the problematic phrase crossed out and replaced with the second, more capacious one, one that still replicates a binary (non) choice.

Home Alone

Life is not really how I imagined it. I am a newly-minted Assistant Professor, flush from my encounter with the dreaded academic job market (it was almost as bad as it is now, applications to PhD programs came with peel off-warning labels, like boxes of cigarettes). I have a salary, which seems like a lot of money to me, since I have been living off a graduate stipend of 5K and a lot of part-time teaching. In my new life I will have undergraduate students for a whole four years, and graduate students for…longer. I will be living alone, in my own apartment, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

If I had known in 1984 that adulting could be a word, I would have used it, smugly.

Ignorance

It has been almost three years since the first installment of “Homing,” written from the makeshift desk my husband built in a corner of our bedroom during COVID lockdown. That desk, with its sometimes fraught but intimate relation to the domestic spaces around it, still stands, although now I take my writing, unmasked, to a variety of public spaces. My laptop is once again itinerant, catching when it can a whiff of the internet under the trees on the Rice campus, or locking into place as part of my office furniture. The surface of the desk “back home” is now mostly covered with books for other projects, among them what I hope will be a brief history of, and a series of meditations on, gynophobia.

Easter Egg Hands

With six days to go, and a delivery of duplicate supplies scheduled for tomorrow, I have, for the first time in my life, failed to make Easter eggs. Perhaps I should say, I have failed to realize my vision for this year’s eggs. Ironically, this is also the first time I have really planned ahead. This was to have been the year of indigo eggs. As early as last summer, I planted Japanese indigo, whose leaves when crushed produce the dye that has become the name of that wonderful, perfectly mid-shade blue we see in so many South Asian fabrics. When the plants died back in this winter’s unusual-until-climate-change hard freeze, I hovered anxiously above the little patch of ground by the front steps, scanning for nondescript leaves and unremarkable small white flowers. It was only last week that I became confident that I would have a crop of leaves big enough to fill my blender jar.

Kitchen Mess

The kitchen is a mess, as it almost always is. I cannot write these words without hearing myself say them aloud. The sentence I hear in my head can be spoken with different emphases: like the narrator in George Eliot’s Middlemarch, who lets us hear different versions of Rosamond, the anti-heroine’s, question “what can I do?”. I let myself hear, alternatively, the kitchen is a mess, the kitchen is a mess, and the kitchen is a mess. The first singles out the kitchen as place, perhaps announcing its centrality to the household and to the definition of what constitutes a mess. The second reflects, or perhaps wearily anticipates, a protest, say, from a family member, that the kitchen is not as messy as I think. This version of the sentence follows, or perhaps presages, “it looks fine to me.” The third, I think most common, form of this utterance emphasizes and lingers on the idea of mess itself, conjuring in its spoken rhythm a series of sensory images: cluttered counters, dirty dishes, and sticky floors.

Wilderness

I think of Capability Brown, of Jane Austen, and Fanny Price, every time I walk from my office building at the center of the Rice campus to the Medical Center on Houston’s highly trafficked Main Street. Maybe twenty steps from my building, there is a path that runs along the side of Weiss, one of the university’s eleven residential colleges. As you pass the college on the left, perhaps pausing to notice a small vegetable garden that has lately been swallowed by weeds, you enter what feels like a liminal space of wildflowers, overgrown bushes, and fallen trees.

Holiday Disasters: Keeping Christmas

I am on sabbatical, so I do not have to take a dependent care leave to be with my mother as she is being treated in New York for congestive heart failure, and later, for lung cancer. I say treated, but there is little treatment and less care at the NYU hospital about ten blocks from my mother’s apartment. Hospitals are full, a fact that the ICU nurses vaguely attribute to the “AIDS crisis.” I have been in New York since mid-October; my son Ross and husband Scott came with me and returned to Houston so Scott could finish out this semester of teaching. There is as yet no Zooming, which, 30 years later, when the hospitals fill again, would have allowed him to stay with me. Thanksgiving and my birthday are a blank to me. We may have had some faint celebration, perhaps a turkey, but only if Scott had been there to cook it. For all I know, or remember, Scott and Ross may have been there to perform, in gray, my mother’s favorite holiday.

Holiday Disasters: Boxing Day

It is the middle of December, 1978, and I am pushing my way through the holiday crowds. I carry with me the bodily memory of other Christmases: the feel of the cold air on my bare head (I have always resisted hats); the smell of gas and greenery, the heft of my purse tightened across my body against mugging; my sense of agility as I move from gap to gap in the moving forest of taller people. There is a soundtrack to my movements, but it is only this year that I stop midflow to listen to it. Over the honking of taxis and the groan of busses as they pull up to curb, comes the sound of carols, until this Christmas —the one where my father is in the hospital, dying, a few blocks away—mere background noise.

Holiday Disasters

It all has to do, once again, with hosting. It starts, as the holiday season does or should do, with Thanksgiving, and with the new post-Harvey house, to which we moved to escape not only the dramatic vulnerabilities of flooding, but also the small and accretive domestic challenges of living in an older home. The brand-new house, finished days before we moved in, would, we thought, change our relationship to homing entirely: we would, for an unspecified number of years inhabit a space with grace and dignity. My husband would not have to lay pipe in the torrid humidity of a Houston August; we would not constantly be looking at cracks in the plaster of our walls for evidence that the foundation of our house had moved; we would not constantly be calling repair people after hours; we would not have a list of homing to-dos so long that it lived with us like a ghost, like another household member.

Cashmere

The last picture on the wall is a gift from my elder son, an enlargement of a studio shot of my mother in her late twenties or early thirties, stretched across a large wooden canvas. As a smaller, but still quite large photograph, it stood, unframed, and a little dog-eared, on my bureau or my desk in many different apartments and houses. When I moved to a new place, it was a ritual art of settling in to find a place in my bedroom for the “Gladys picture.” I have many pictures of my mother taken when she was around that age, because her job as, what I must have misspelled many times on various applications throughout my childhood, a “photo-liaison officer” for the United Nations, meant that she was always around cameras. I love all those photographs: the one of her in a bathing suit looking demurely down as the camera takes in the beauty of her naked skin; the ones of her dressed for work (she was one of the first women to be photographed around Arab delegates with her head uncovered); the one, a little later, of her pregnant with me, a glass of wine in one hand and a cigarette in the other. But this picture is for me, and for my family, the true “Gladys picture,” indeed the one that allowed me to call her “Gladys,” if at first only to myself.

Thanksgiving: Inside the Box

It is harder to describe the process of making the cake than it is to make it. My mother and I would each take a cookie in our left hand and, using our right hand, would cover it with whipped cream flavored with vanilla and sometimes chestnuts. We would then add another cookie, and alternate whipped cream and wafer until we had a mini-stack of four (for my smaller hands) or five or six (for my mother’s larger ones). The cookie and cream stacks might slip a bit, but we would flip them sideways and coax them into position, end to end, at the bottom of my mother’s frosted glass dish with an engraving of a dog on it. We would then stack again, adding to the end of the growing log until we reached the end of the dish. I was always the one to cover the entire vertical stack with cream, smoothing it with a spoon until no glimpse of wafer was visible. Then I would swirl the top with a spoon, adding grated chocolate or coco—or one adventurous year, canned cherries in syrup carefully dried so they would not bleed into the cream.

MyChart

You are at your kitchen table in the early morning, avoiding checking your email, as you have often vowed and usually failed to (not) do. Perhaps you are on Facebook, Twitter, or on what remains of your newsfeed after refusing to renew your Apple Plus subscription in a vague but admirable attempt to be “more present.” Perhaps you are doing something less guilt-inducing like browsing Thanksgiving recipes, or something more important, like writing a to-do-list, a novel, a blog post. As, for example, you ponder the problem of too many side dishes and too little oven space, an email alert pops up. “You have a test result from MyChart.” How this alert registers, how it sounds, looks, and feels to you, depends in part on how anxious you are about the test(s) you have taken. This email could be anything from the faint echo of a routine check-up to an answer to prayer. Even in the first case, you realize as you do or do not open the email with the test result, that the medical world has reached out into your home to touch you. The surge of adrenaline—small or large, depending—transports your body from your kitchen to the doctor’s office, to the lab, to the mysterious non-place of MyChart.

“This is the true nature of home—it is the place of Peace; the shelter, not only from all injury, but from all terror, doubt, and division. In so far as it is not this, it is not home.”- John Ruskin, 1865

“For many women and girls, the threat looms largest where they should be safest. In their own homes... We know lockdowns and quarantines are essential to suppressing COVID-19. But they can trap women with abusive partners.” – UN Secretary-General António Guterres, 2020